Life, personal and professional, is in many senses a balancing act. This is also true of growth and economic policy.

Central banks must balance any need to hike rates to combat inflation with the danger of pushing their economies into recession. To make the right decisions, the Fed and its peers need to have both the correct data and the ability to assess it against both their specific needs and given mandates (which may include employment/growth as well as inflation control). The Fed currently faces particular challenges, for example, in assessing changes in financial conditions and to what extent they are due to policy tightening – or to other factors such as the regional banking difficulties.

Investors also need to perform a balancing act. Tactical decisions based on short-term market moves are not a sustainable source of performance; they need to take place within a strategic asset allocation (SAA) that is based on a broader assessment of structural economic and investment change.

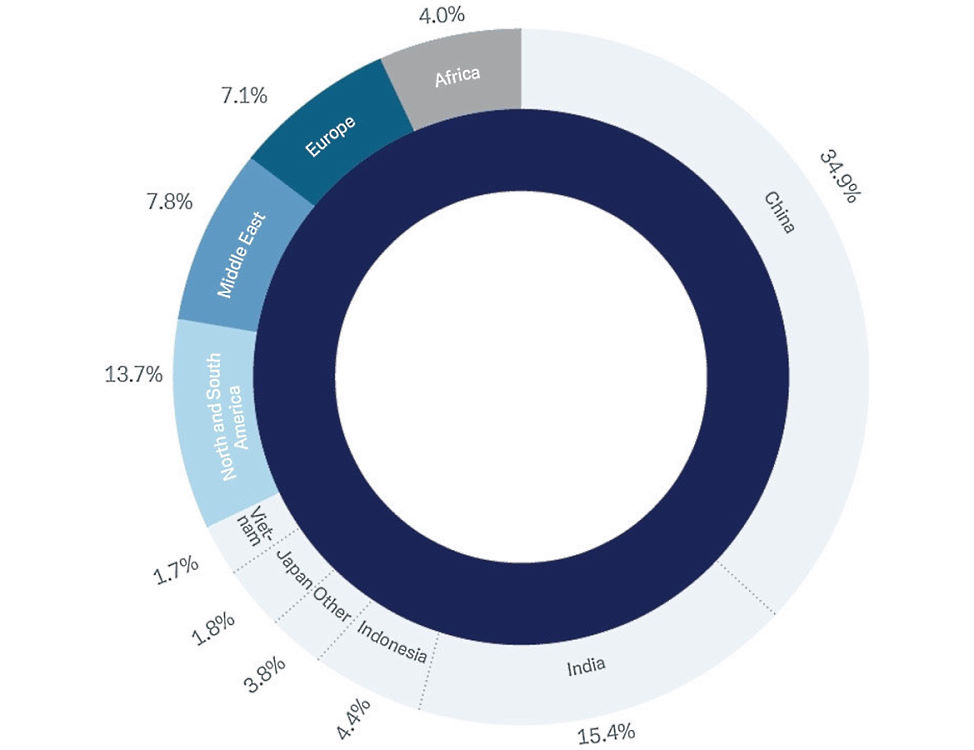

This year, growth should mainly come from Asia: after an uneven start, China’s recovery is likely to strengthen in the second half of 2023 before slowing in 2024. By contrast, our base case for developed markets is a shallow recession or a period of only anaemic growth in 2023, followed by a modest recovery in 2024. Weak developed markets’ growth combined with persistent inflation may increase the risk of policy overtightening, as could any misreading of the apparent current strength of many countries’ labour markets.

We expect the Fed funds rate to peak soon at 5.25-5.50%, and the ECB deposit rate to rise (somewhat later) to a high of 4%. But a possibility of yet higher rates, and remaining inflation worries, mean that government bond yields are likely to rise further. Our central forecast is for 10-year U.S. Treasury yields of 4.20% and 10-year Bund yields of 2.80% at end-June 2024 – and they could go higher in the interim. Investors need to be prepared for re-steepening curves or less inverse curves within the forecast horizon.