Philanthropist Julie Packard, the force behind the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, has been one of the greatest pioneers in ocean conservation for more than 35 years. She speaks about how plastic pollution only comes third on her list of ocean priorities, behind climate change and sustainable seafood; about the importance of foundations, and how she has just embarked on a programme of inspiring the next generation of scientists.

There is little in Julie Packard’s background to suggest that she would become one of the greatest saviours of the world’s oceans. Packard, one of the daughters of Hewlett-Packard founder and electronics billionaire David Packard, was brought up in what is now Silicon Valley, California, separated from the Pacific Ocean by the Santa Cruz Mountains. There was no great aquarium down the coast at Monterey Bay until she and her sister persuaded their parents to build one; and while her family is steeped in engineering and science, there was no marine history to speak of.

Yet Packard says her childhood, surrounded by nature, was the inspiration for everything she would do. “In the 1950s, what is now Silicon Valley was quite rural and my father, even though he became a very successful business person, had grown up in Colorado on the edge of the prairie. He was at heart a rancher and he wanted to be outdoors. I grew up in an apricot orchard, and all that became part of my values.

“Then there was a huge economic boom in California, and as a teenager in the 1960s the environmental movement there was front and centre. I knew I wanted to study biology because I was fascinated by living things. For me it wasn’t an epiphany [about saving the oceans], it was a deep love for and engagement in nature and concern about its protection, and you can’t talk about saving nature without saving the oceans. Back then, there was little focus on ocean conservation.”

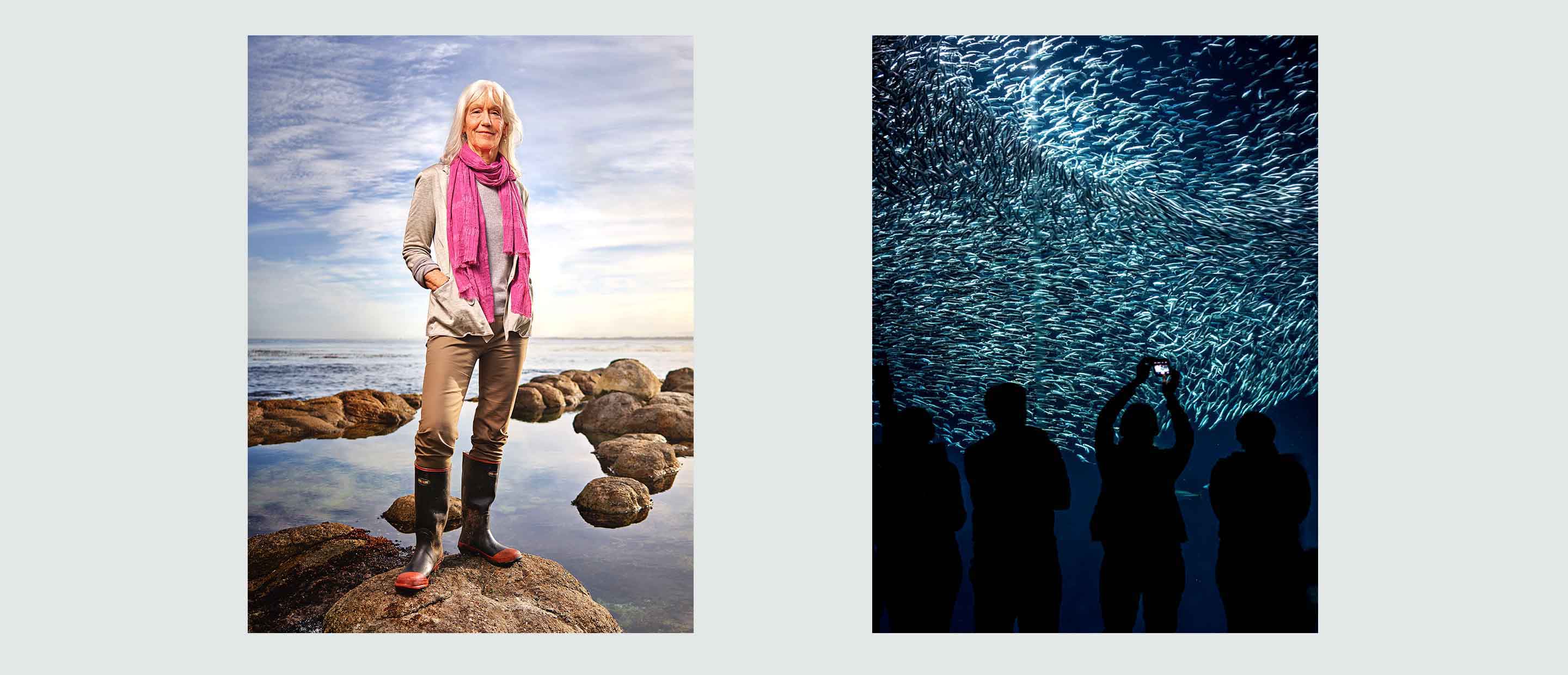

Packard became a marine biologist, and a little over half a century later the institution and teams she leads have revolutionised significant elements of humankind’s relationship with the oceans, and spearheaded some of the most effective elements of their conservation and rebirth. As Executive Director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium since its opening in 1984, she has spearheaded the protection of numerous essential sea life forms, from kelp to jellyfish and sea otters.

The aquarium, one of the biggest tourist attractions in the San Francisco/Silicon Valley area, simultaneously provides amusement to visiting families, adults and schools (there’s nothing quite like tickling a manta ray), protection of endangered species, and a wide-ranging and ambitious programme of education for a next generation of scientists. It recently opened the Bechtel Education Center in a spectacular new ‘eco’ building nearby, with a mission to “inspire the next wave of ocean leaders”. The Center is spread across four storeys and 2,400 sq m, including four learning labs, collaborative learning spaces and facilities for students and scientists to meet and interact. All of which is part, Packard says, of the long-term plan of the Aquarium.

“We are realising the imperatives that the next generation grow up with solid grounding in science but also a sense of agency and confidence with environmental issues – now more than ever we need leaders and now more than ever we need a stepped-up education programme. The Bechtel Education Center is a big project and we have a number of new learning spaces and laboratories and we are going to be running leadership development programmes. The public school programme in the US is quite lacking in science education.”

Packard is passionate, yet somehow dispassionate, in the best possible sense, at the same time. She speaks with great fluency and enthusiasm about the projects the aquarium is spearheading; yet you sense she is not one to let emotion get in the way of the facts. A true scientist, in fact.

Packard adds that she is enthused and inspired by the latest generation to approach adulthood. “Young adults are the most optimistic about the possibility of changing the world – the youth activist movement about climate we are seeing right now is incredible and a demonstration of that. Being land dwellers, our focus has always been on land. Only in the past quarter of a century have people started to realise that the ocean is critical and amazing in its own right.

“Awareness that climate change and the ocean’s health are linked is absolutely key. The ocean is a huge part of the system that enables life to exist here, and that connection, how climate change is damaging the ocean, and how a healthy ocean is a fence against damaging climate change, is fundamental.

“People don’t always make that connection at the aquarium but it’s one thing we are trying to build awareness of: the idea of how the living ocean is a driver in our global climate system, how it has absorbed 90 per cent of the excess heat and 25 per cent of excess carbon since the industrial revolution. Without the ocean, earth would be 20 degrees hotter than it is today by one study. That requires a living ocean not a dead ocean, because it’s all done by little microscopic plants taking CO₂ out of the atmosphere at a huge rate.”

Will the private or public sectors need to lead the way, globally, in ocean conservation? “I believe solving global climate change requires action from both sectors. Some of the polling I have seen is interesting. People in the US tend to think the private sector will have a bigger role and some appear to believe technology will solve all the problems. In Europe people put it squarely on the public sector. Regulations are absolutely necessary and at the same time solutions driven by industry are huge, too.”

For Packard, ocean conservation is not an issue that can be separated from climate change: indeed, for that reason, she answers questions about ocean conservation with answers about how to deal with climate change. When asked what the biggest challenges specifically facing the oceans are, she does so with her usual scientist’s logic, listing four in descending order of importance: global climate change; sustainable seafood; plastic pollution (“Is it the biggest threat? No, climate change and overfishing are much bigger in my opinion, but it is still a critically important issue”); and ecosystem damage and habitat loss.

“The initiative I am most involved with is what the Aquarium is doing on sustainable seafood. Our Seafood Watch programme defines sustainability standards and criteria and our team has rated over 2,000 fisheries, and began with the idea of driving market demand for sustainable seafood by raising awareness among consumers for seafood in the US.

“All that demand and media attention has grown in the past 20 years – these changes are a long haul. By building consumer awareness we got media attention, which got the attention of businesses. Then retailers want to improve their practices and ratings.” She says 85 per cent of seafood retailers in the US have committed to bring their products into their sustainable seafood rating system: Seafood Watch is the biggest system of its type in the world. The system is international: for example, more than 100,000 shrimp farms in Vietnam have signed up to Seafood Watch standards.

She says this, for her, is a key part of the blue economy. “It is an imperative that businesses really step up in terms of doing no harm, but more importantly they must also add value to our progress on sustainability. When the blue economy is mentioned, the first thing that comes into my mind is aquaculture, which is and will continue to be a very important part of global food security. It can be done well, but also can have really harmful impacts… So, what investors can do is push for sustainability. The two biggest [focuses of attention] are farmed salmon and shrimp, the highest-volume seafood items that Americans eat. Our team and other NGOs are working to address sustainability issues raised by these. It’s going to continue to grow as a piece of our blue economy.”

Starting a foundation

My parents set up The David and Lucile Packard Foundation back in the 1960s and we celebrated its 50th anniversary recently. It is now one of the largest family foundations in the US, as well as one of the biggest environmental philanthropy funders. [My advice is] that if you have the resources, find something you care about and contribute to that in whatever style you prefer. Some people really like investing in people. Some philanthropists like out-of-the-box thinkers, others have a more strategic decision-making system. There is so much wonderful work that foundations can support because they can take risks. Businesses have a different goal, foundations have an incredible role to play in facilitating things to happen that neither government nor business are going to be able to do on their own.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of LUX Magazine. This issue features the first in a series of Deutsche Bank Wealth Management/LUX supplements about our ocean and its importance to both the environmental and economic wellbeing of the planet.