Impact #4: The new world order – winners and laggards

• Asia moves ahead • Developed world divergence? • Multilateral goes regional • Currencies reinvented

Changes to the how individuals and companies operate, and individual governments’ policy responses, will be accompanied by changes to the international environment as, over time, we move towards a new world order.

The immediate world economic outlook is to a great extent dependent on how quickly vaccines can be produced and administered. Our assumption is that we will get broad vaccination in the developed markets from Q2 2021 onwards after priority use in Q1. Vaccination should avoid the need for further mass lockdowns, at least after mid-2021. Pent-up demand and high savings rates will boost the economic recovery, although it is likely to be de-correlated between economies, at least initially.

GDP growth rates are expected to be positive in 2021 after economic contractions in 2020. Forecasts are given on page 26 in the report linked to below, but exact numbers here will be less important than the structural changes that underlies them. Two questions will remain particularly relevant. First, how long- lasting will be the COVID-related damage? Second, how will the pandemic affect economies’ relative economic strength?

The long-term impact of the pandemic may be less severe than the global financial crisis (GFC) as this crisis was caused by an exogenous shock (the virus) rather than internal economic imbalances. Fiscal and monetary policy also reacted more quickly than during the GFC preventing more and worse “second round” effects, for example through the broad introduction of furlough schemes to preserve employment. Even so, we think that the U.S. will not be back to pre-crisis (Q4 2019) levels of output until the end of 2021 or early 2022 and the Eurozone will have to wait until 2022.

Result #1: Asia moves ahead

In contrast, the Chinese economy expanded by an estimated 2.2% in 2020 and is forecast to grow by over 8% in 2021. Many other Asian economies have also done relatively well, with the obvious exception of India (estimated to have contracted by -9.5% in 2020, before an expected expansion of 10% in 2021).

The rise of Asia (in the modern era) is not a new story – it can be traced back over 40 years, to the start of economic reforms in China in the late 1970s, or perhaps even further. The pandemic, here as elsewhere, has simply accelerated an underlying trend. Chinese growth at a time of U.S. economic setback potentially brings forward the time when China’s GDP exceeds that of the U.S. China has already marked the end of 2020 with the signing of a major Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the formal release of its next five year plan in March 2021 will give it another opportunity to define exactly where it wants to go from here.

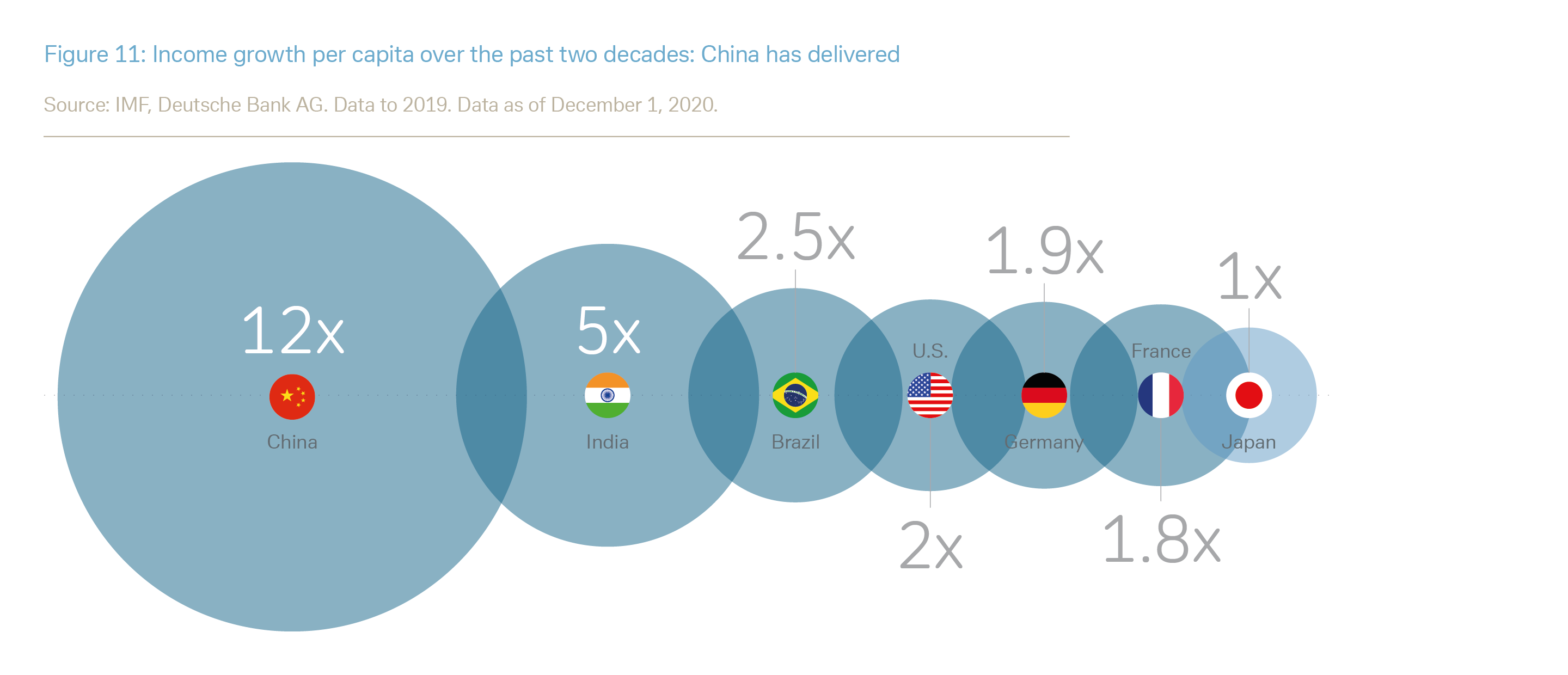

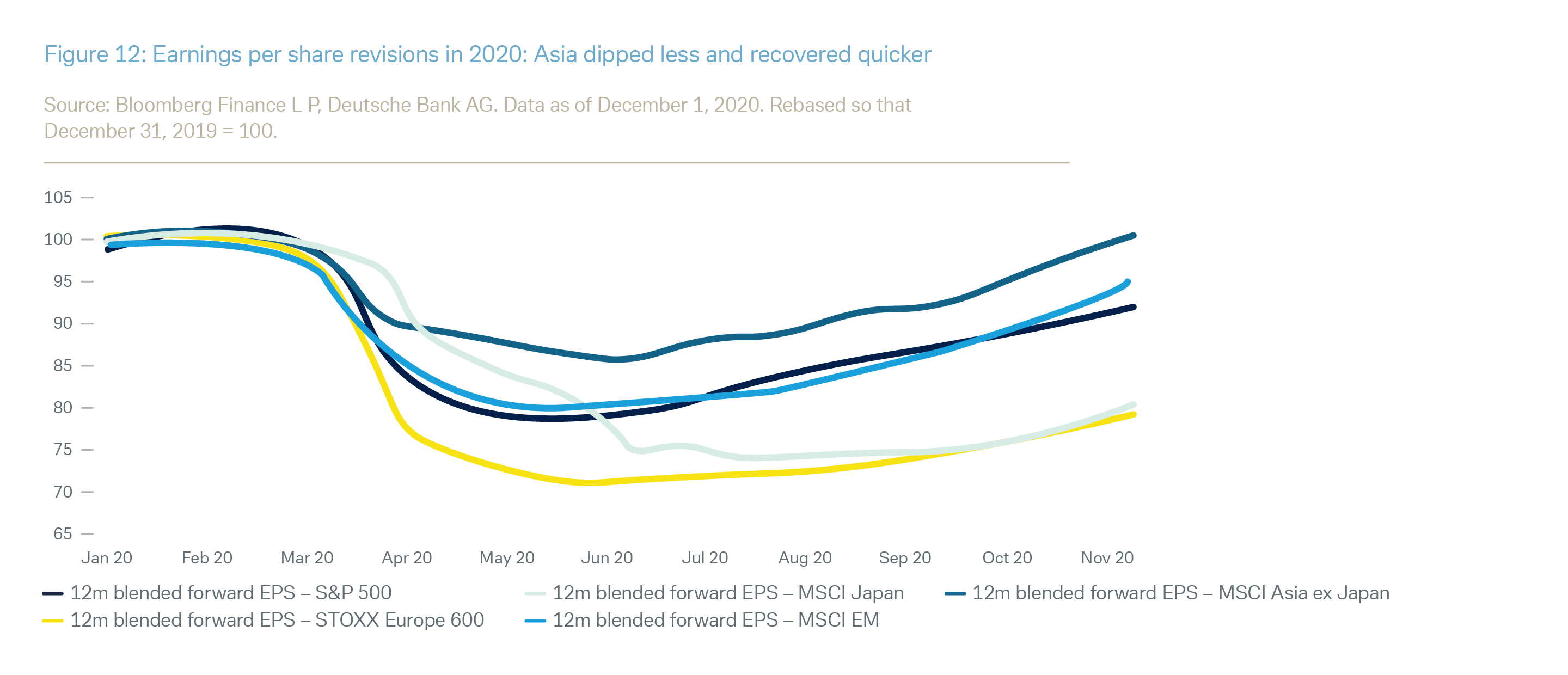

These long-term relative shifts in regional economic power are nothing new, and in recent decades have been manifest in divergent trends in income growth per capita (Figure 11). But short-term relative changes also have an impact. A faster Asian economic recovery will have an immediate impact on the health of EM corporates, where earnings per share estimates are already close to pre-crisis levels, unlike their developed market peers – as Figure 12 illustrates. This adds to the case for emerging markets equities and bonds in 2021, and also in the longer run the importance of emerging markets cannot be ignored.

Result #2: Developed world divergence?

By contrast, many developed markets start 2021 with quite a lot to prove.

The U.S. election outcome will have multiple implications for economic growth. Some form of fiscal package is likely, and the Senate run-offs in Georgia on January 5 will set out a starting point for the policy agenda (through determining which party controls the Senate). We think that there will be continuing pressure for higher taxes, which the Senate may well accede to, but the Fed policy regime change will help to keep monetary policy accommodative, and the U.S. has a good track record in recovering from crises.

In the longer run the flexible and dynamic nature of the U.S. economy will continue to be supportive of its recovery, and while the focus will be on the struggle between China and the U.S. to be the world’s leading global economic power, it is worth also considering possible divergence between major developed markets.

The Eurozone’s outlook certainly appears problematic. The European recovery fund should help mitigate to some extent intraregional divergence, once it starts to be implemented in 2021, and shows the potential for European integration. Divergence between and within Eurozone countries will remain a real concern, however, as will (for some of them) levels of debt. The recovery fund is seen as major game changer by many as grants under the scheme would mark a big step from austerity to solidarity. But how the divergence question will be fully addressed in the absence of another external shock remains unclear and the current dissonance between some Eastern European economies and the remaining EU members could be a foretaste of troubles to come. Brexit, now moving toward a possibly disorderly conclusion, shows how disruptive centrifugal forces can be. In the longer run the EU needs to find an answer to the divergence issue, and to the implications of its underlying demographics of an ageing population (in contrast to the U.S.). Digitalisation may provide some signs of progress, however: we may get a decision on the introduction of a pilot project for a digital EUR in the ECB’s Strategic Review, due to be announced mid-year.

Result #3: Multilateral goes regional

At the start of the coronavirus crisis there was much talk of severe disruption to global supply chains. In the event, disruption was rather less than many had feared and talk of deglobalisation may be overdone. However, more subtle changes have been taking place, with firms rethinking supply chains, often in favour of more local partners. (Brexit may also have prompted some re- evaluation, on a much smaller scale).

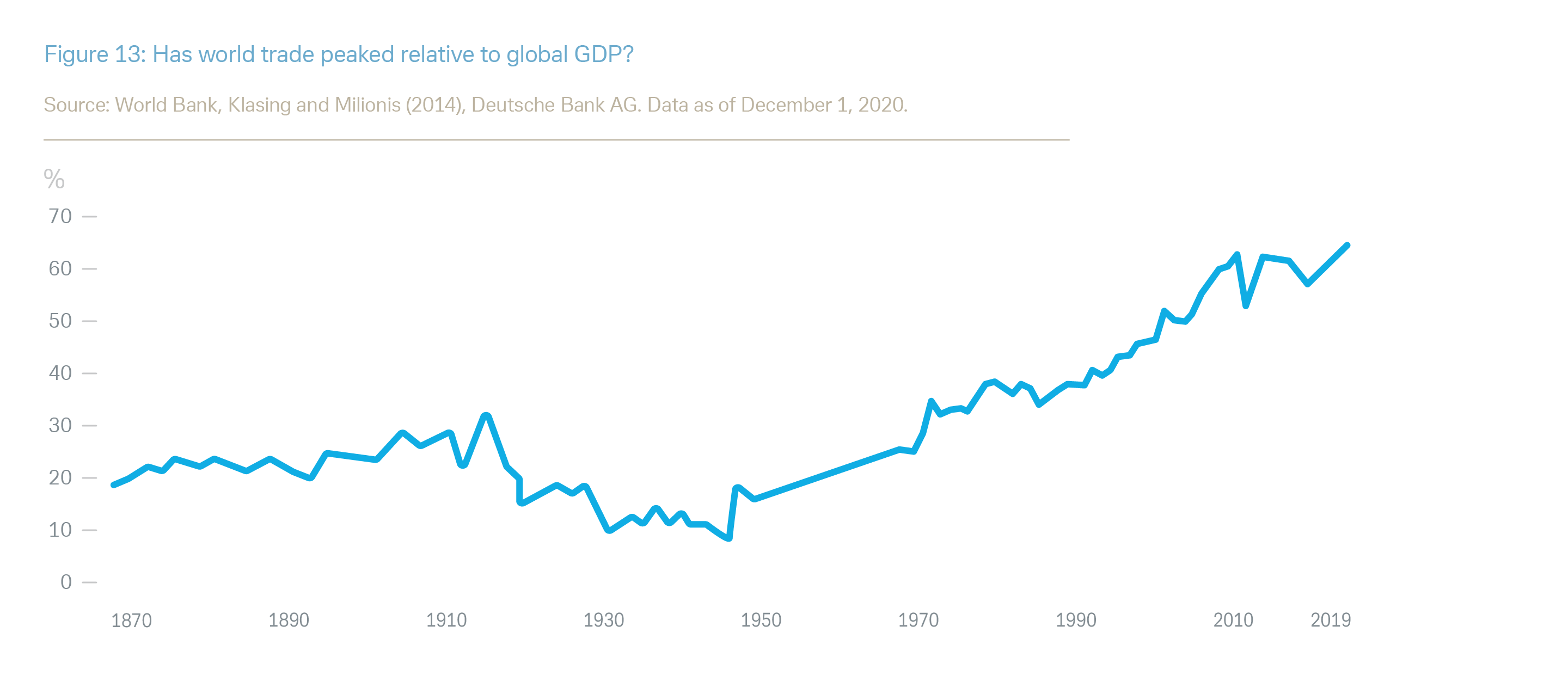

Global trade growth was already running out of puff before 2020 (Figure 13), and the ratcheting up of U.S./China trade tensions long predates the pandemic. But what is new is the rise of new regional agreements without even a notional U.S. presence.

The November 2020 signing of a regional comprehensive economic partnership (RCEP) between China and 14 other Asian and Australasian countries encapsulates this trend. The RCEP (reached after eight years of negotiation) promises to improve trading ties in the region, mainly through sharp tariff reductions (or removals), although published timelines and data are still sparse. We do not expect any transition to a region-based system (here or elsewhere) to be quick or smooth. Trading partners can fall out over the detail and there will be justified concerns over the dominance of China in RCEP and the region generally – India has been suggesting that firms should follow a “China +1” strategy for suppliers. Digitalisation also opens up new areas for concern in trade or other relationships (e.g. around pharmaceuticals): cyber security is one of our key themes.

The need for a well-functioning multilateral global framework also remains. The threat of trade conflicts across (or within) regions remains, and the extension of “buy local” policies, as advocated in the past by President-elect Biden and others, is also a potential concern. Even more importantly, a multilateral approach will remain necessary to deal with the challenges posed by environmental, biodiversity and climate change issues – relevant to our key investment themes on ESG, resource stewardship and the blue economy.

Result #4: Currencies reinvented

We could also see a change in perceived currency dynamics. Currencies are usually seen as being driven by multiple factors, both short (e.g. interest rate differentials) and long-term (e.g. relative economic growth). Coronavirus changed this perception in 2020. From March onwards, most major currency pairs were driven largely by changes in overall market sentiment. So, for example, when markets went risk-off on heightened coronavirus fears, demand for USD as a safe-haven currency increased and the currency appreciated – despite a faltering U.S. economy and highly accommodative Fed policy.

Will a return to a more normal economic environment and more consistently risk-on markets reverse these trends, weakening the USD? We would not expect a dramatic shift. A return to a more normal operating environment may ease the link between overall market sentiment and currency movements and perhaps the most important pair for the USD – vs. the EUR – may end up being driven also by weakness in EUR, if Europe's political problems are not resolved. As a result, our end-2021 forecast for EUR/USD is 1.15 – implying a stronger USD than in December 2020.

Other long-term currency trends may be more profound. Watch for example developments in the long-term internationalisation of the CNY, with it perhaps becoming a more important reserve currency in some countries with deep links with China. Digitalisation, in the form of CBDC, could also have an impact on global FX markets in 2021 and beyond.

Consequences

- Global economic leadership to change.

- Digitalisation to change the way we deal with currencies.

- Strategic asset allocation (SAA) remains key.

Our full CIO Insights report “Annual Outlook 2021: Tectonic shifts" includes our new macroeconomic and financial market forecasts for 2021. Please refer to the Important Notes at the end of the report for disclosures and risk warnings.

To download a printer-friendly PDF of the full report, please click here.

To view a mobile-optimised version of the full report, please click here.