Venture Capital investing: what is it?

Our CIO Special on venture capital investing examines: • Growth in this area of investment • The wide range of risks involved • Diversification and its potential role in portfolios

Please note: this article is more than one year old. The views of our CIO team may have changed since it was published, and the data on which it was based may have been revised.

What is Venture Capital investing?

Firms need to be funded from start-up to profitability. But young firms may find it difficult to access conventional sources of finance, given their unproven nature and low visibility.

Instead, Venture Capital (VC) investing can provide funds in exchange for an equity stake in the business, with the Venture Capitalist hoping that the investment will yield a high potential return.

Venture Capital firms mostly invest in start-ups with high growth potential – in contrast to private equity firms that usually buy into more mature companies.

Venture Capital can be set up by “angel” investors, i.e. high net worth individual investors, or can be private capital organized as a company or institution. Alternatively, Venture Capital can be delivered through specially set up subsidiaries of corporations, commercial bank holding companies and other financial institutions. In the latter case, there may be objectives beyond high returns – for example the development of a technology – that bring synergies to both the corporate and the Venture Capital firm. The main focus of this report is, however, on general Venture Capital funds.

A brief history

Until the 1940s, investments in private companies were the prerogative of wealthy individuals and families. In 1946, the American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC), likely the world’s first institutional Venture Capital (VC) firm, was founded by Georges Doriot. The firm raised USD3.5mn supported by MIT, University of Pennsylvania, University of Rochester, Rice University and many financial institutions to back new Ventures in the science and technology spheres.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of private VC firms on the U.S. West Coast at the same time as the development of the semiconductor industry in Silicon Valley. In 1979, the U.S. Labor Department allowed pension funds to include alternative assets in their portfolio mix. Consequently, big capital began flowing into the VC industry. In 1978, 23 Venture funds managed about USD500mn of capital. By 1983, there were 230 firms overseeing USD11bn. VC also moved from a focus on semiconductors and data processors to include sectors like personal computers and medical technology and was seen as a factor behind the dotcom bubble that ended in 2000: large investments were made in fledgling tech companies that, in retrospect, had only a very slim chance of success. Venture Capital fell out of favour in the years following the tech bubble collapse.

In the last decade or so, however, the internet has produced a range of companies with sustainable business models. The rise in big tech firms has been accompanied by (often tech- driven) advances in other areas such as healthcare. Venture Capital firms have found themselves well positioned to capitalize on the opportunities and we discuss recent growth in the industry below.

Life cycle of a VC investment

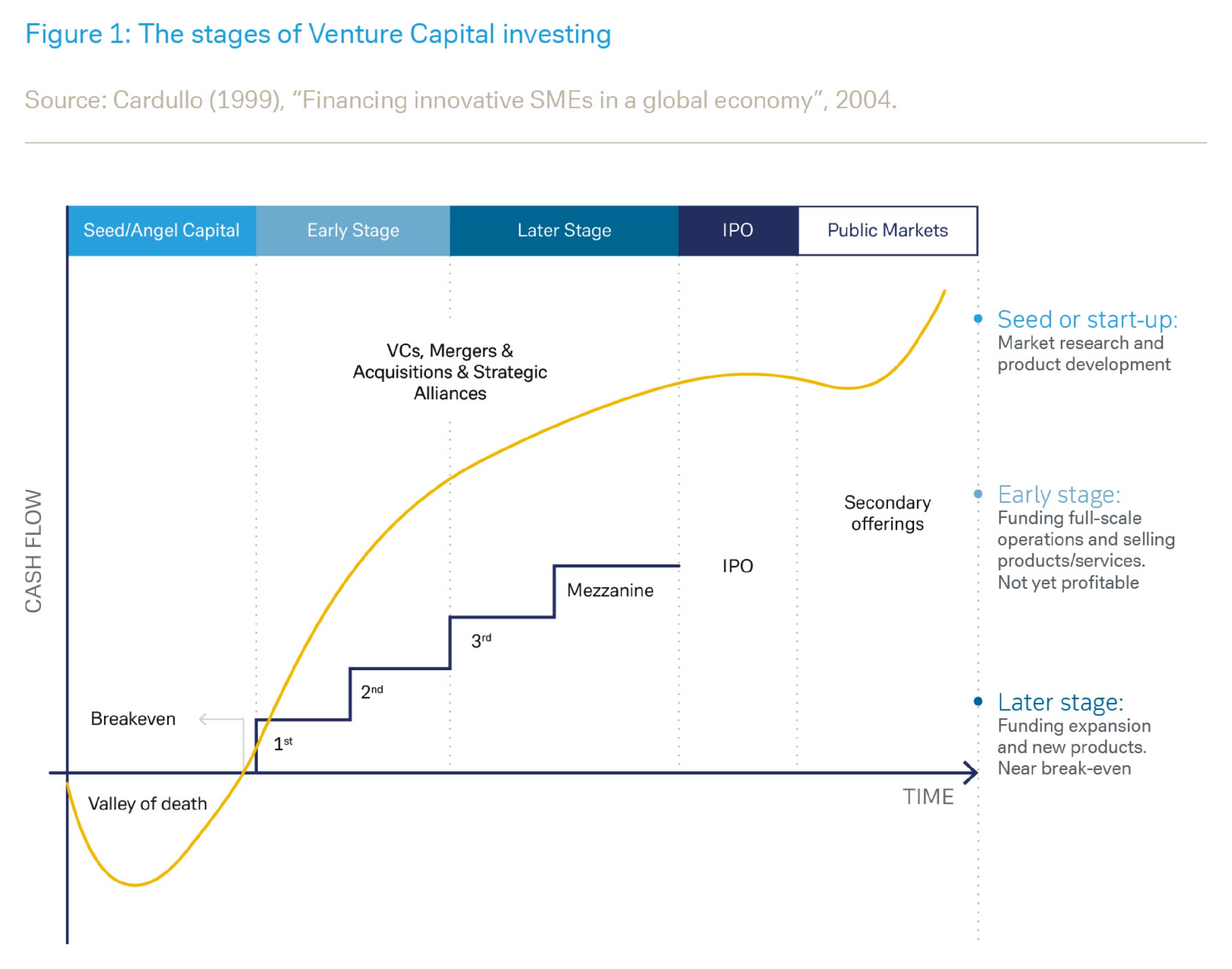

The key stages of Venture Capital financing are shown in Figure 1. Exact terminology may vary slightly, but “staged funding” is the key concept here. Rather than providing funding upfront, staged funding allows Venture Capitalists to regularly refresh information about the firm, monitor its key metrics, review plans, and evaluate whether to provide additional capital funding or look for an exit.

"Staged funding is the key concept here. This allows Venture Capitalists to regularly evaluate whether to provide additional capital funding or look for an exit."

- Seed financing: “Seed” capital was historically provided to many firms by friends and family, but recently has been regarded as the first institutional funding round in a start- up. Seed funding is mainly invested in research and development, continuing to build out the company's initial product. Companies at this stage are often characterized by severely negative cash-flow: seed capital needs to be sufficient to carry companies through this so-called “valley of death” when many company failures can occur.

- Early stages investing: 1st Stage (sometimes referred to as Series A): Once start-ups have achieved traction in terms of user growth or sales, they are in a position to raise additional funds from an early stage investor. The product is improved as further feedback is incorporated. Amounts of money raised at this stage tend to be several times higher than during the initial seed capital stage.

2nd Stage (Series B): The final “early stage” round: 2nd Stage companies typically have the required product market fit by this stage and have strong user growth, if not revenue. Companies often raise capital for investing in sales and marketing to help scale up the product for broader markets. Amounts typically raised at this stage are larger still, with some specialist investors perhaps only getting involved at this point. - Expansion or later stage / third stage capital: Once a start-up has reached third (Series C) or later stage funding, it is generally no longer considered an early stage company. Such companies continue to fund expansion through investment in the business. The focus here is on achieving strong growth – perhaps through acquisitions of other potential competitors. The type of investors involved here may broaden out further to include non-Venture Capital specialists as the company is now seen as fundamentally viable.

Mezzanine / pre-IPO financing: Late stage companies at this point typically remain unprofitable and continue to raise capital to fund growth via fourth (Series D) and further fund raisings and ultimately achieve an exit, although some companies may exit before this stage.

The last round of funding before an exit is often referred to as a “Pre-IPO round” (or Series E+). In recent years, such rounds have been dominated by non-traditional start- up investors, like sovereign wealth funds, mutual funds and hedge funds. - IPO or M&A exit: Successful VC-backed portfolio companies traditionally exit in either one of two ways: a sale to a larger company or through an IPO. Media attention is often focused on IPOs, but M&A transactions have been more of a norm when it comes to exit for start-ups of all stages. We discuss SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies) later in the report.

Ultimately, the investors’ aim is usually to realize investment gains at this point – assuming that the company has survived and prospered.

For a brief summary of the report and to download the full PDF, please click here.