Portfolios and Venture Capital

Our CIO Special on venture capital investing examines: • Growth in this area of investment • The wide range of risks involved • Diversification and its potential role in portfolios

Please note: this article is more than one year old. The views of our CIO team may have changed since it was published, and the data on which it was based may have been revised.

Performance vs. public markets

Venture Capital is still under-represented in many private investor portfolios, despite long- standing interest in it by institutional investors and UHNWI (ultra-high net worth investors).

Institutional investors have had good reasons to invest via Venture Capital. Research undertaken by Cambridge Associates (“The 15% Frontier”, 2016) suggests that allocations to private investments might represent a key determinant of long-term outperformance. Its shows that 242 endowments and foundations that allotted at least 15% of their capital to private investments achieved a median annualized return (2005-2015) of +7.6% outperforming competitors with a max. 5% allocation to private investments by 1.5%.

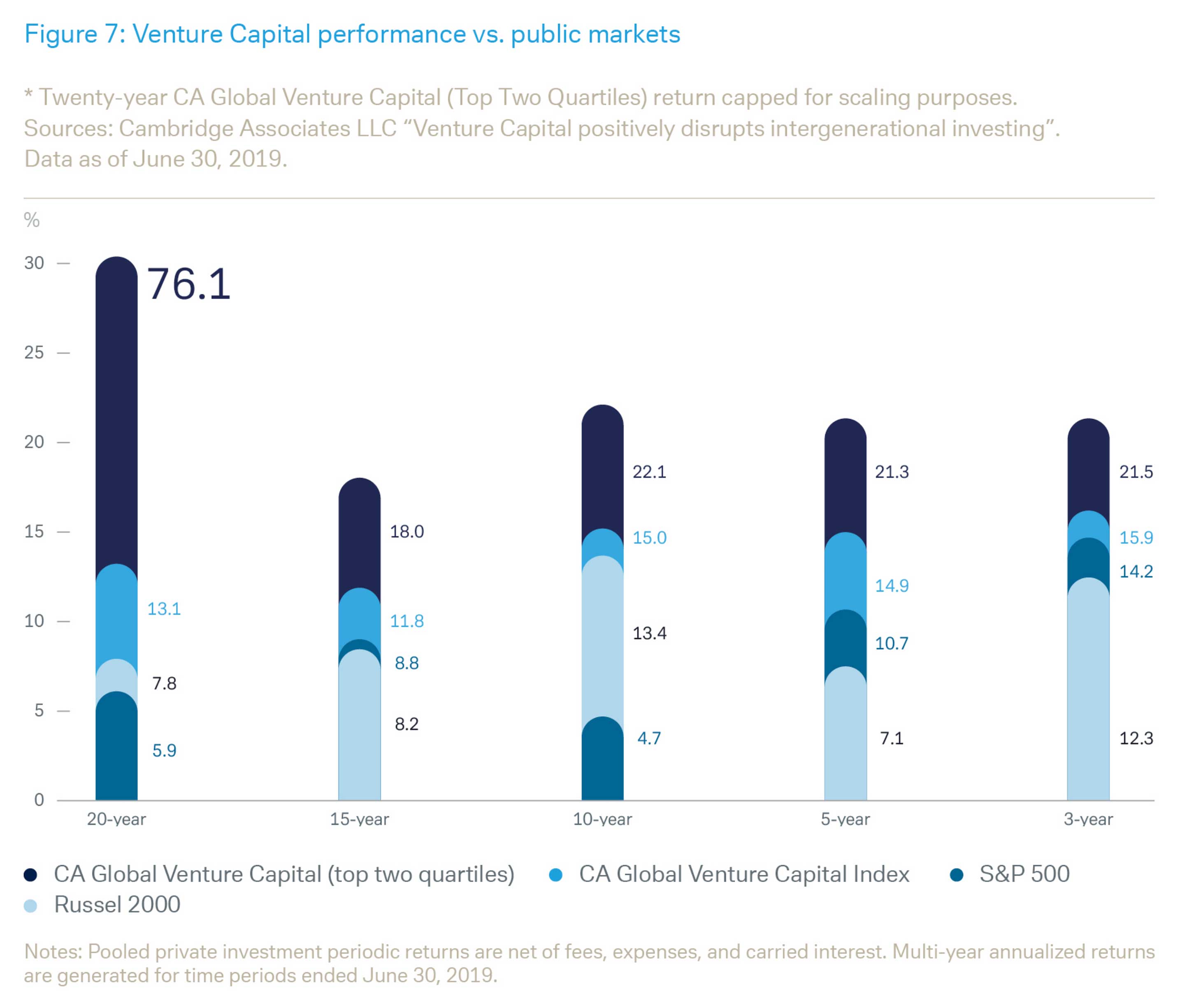

Cambridge Associates data also reveals that in the U.S. Venture Capital consistently outperformed broader equity market indices over the 3-, 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year periods with respective data from recent vintage years backing this picture. As Figure 7 also shows, co- investing alongside top the top two quartiles (i.e. top 50%) of Venture Capital firms has resulted in average annualized returns which are multiple times higher than the public market equivalents over a 20-year horizon (CA Global Venture Capital top two quartiles: +76.1% / CA Global Venture Capital Index: +13.1% / S&P 500: +5.9% / Russell 2000: +7.8%).

Some of these excess returns can of course be explained by the so-called “illiquidity premium” – the need for higher returns to compensate for less liquid investments – but Venture Capital does also seem to be an attractive way of tapping into technological progress and entrepreneurial talent/spirit. Note, however, the need to have a range of Venture Capital investments to guard against individual firm failures, as discussed below.

Possible diversification benefits

Besides offering exposure to evolving industries or emerging transformative technologies, Venture Capital investing can also be seen as offering a natural hedge against risks linked to mature companies/business models which may be vulnerable to disruption.

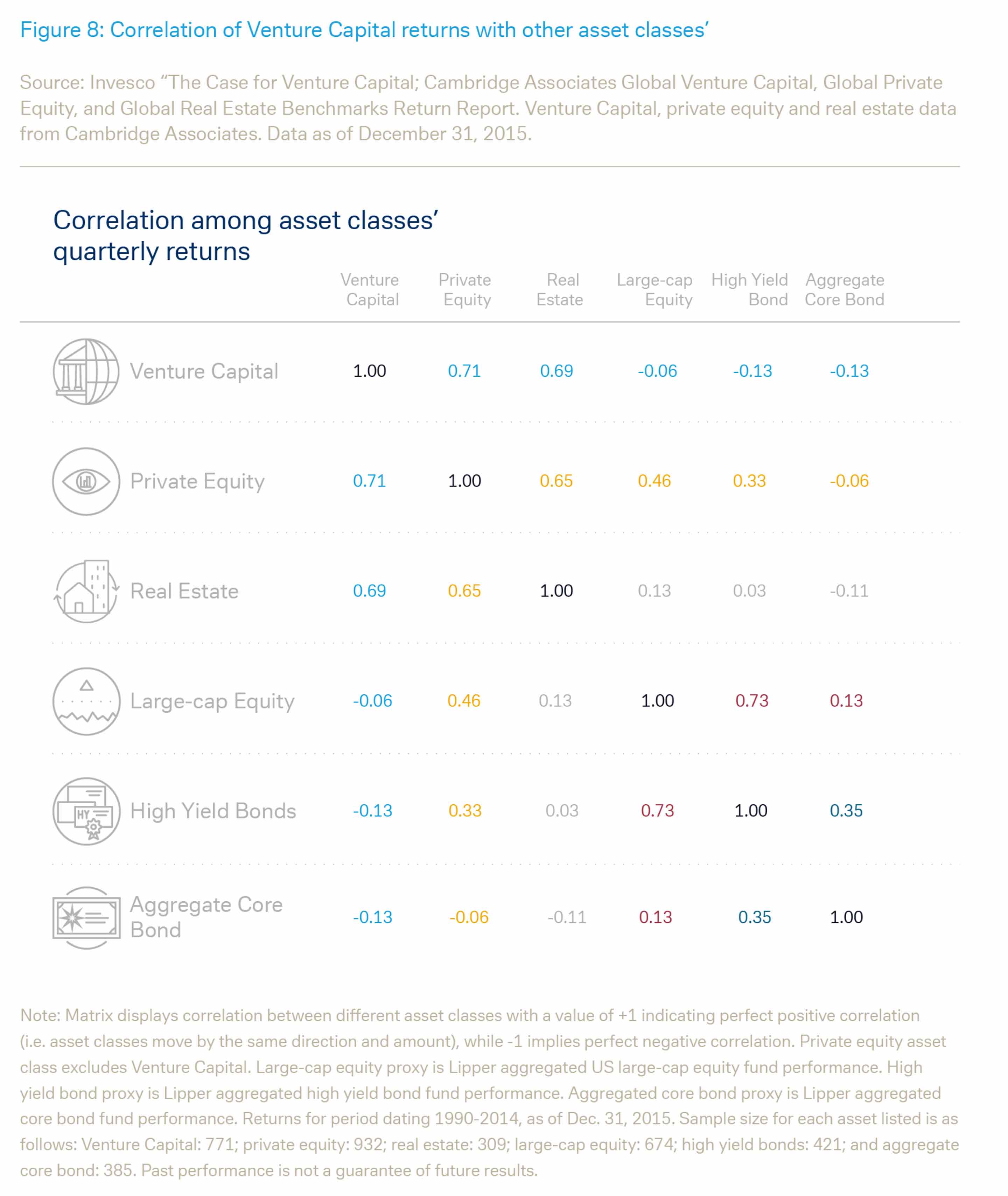

Historical data indicates that Venture Capital returns have been only loosely correlated with returns of other asset classes (see Figure 8) with some research even pointing to an inverse relationship of overall Private Equity and global equity markets.

In a diversification context, it is also worth mentioning that public market equities are no longer as diverse as they once were. The number of companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges has more than halved from its peak in 1996 and the S&P 500 accounts for ~80% of U.S. equity market value. Moreover, 25-30% of the S&P 500’s total market cap is attributable to the top 10 stocks by index weight, with a strong tilt towards Information Technology (which has a 28% weighting in the overall index).

By contrast, the number of private companies has been steadily on the rise during the past decades (comparing 1990-2000 and 2010-2020) but this has not stopped a fall in the number of IPOs. High IPO costs, public markets’ rather short-term nature/focus and the increasing availability of private capital are cited as the key drivers for more and more early stage firms securing funding from private investors, rather than going public. There are still options to engage in small-cap stocks in public markets, but the range of opportunities has shrunk.

It is therefore possible to argue that the private investment market today offers more diversity in terms of industries, technologies and business models than the public market does. Investment portfolios comprising solely of publicly-traded assets will also be excluded from the potential value creation happening between early stages of a company life cycle and an IPO – if the company goes public at all.

"Public equity markets are no longer as diverse as they were. The private investment market may offer more diversity in terms of industries, technology and business models."

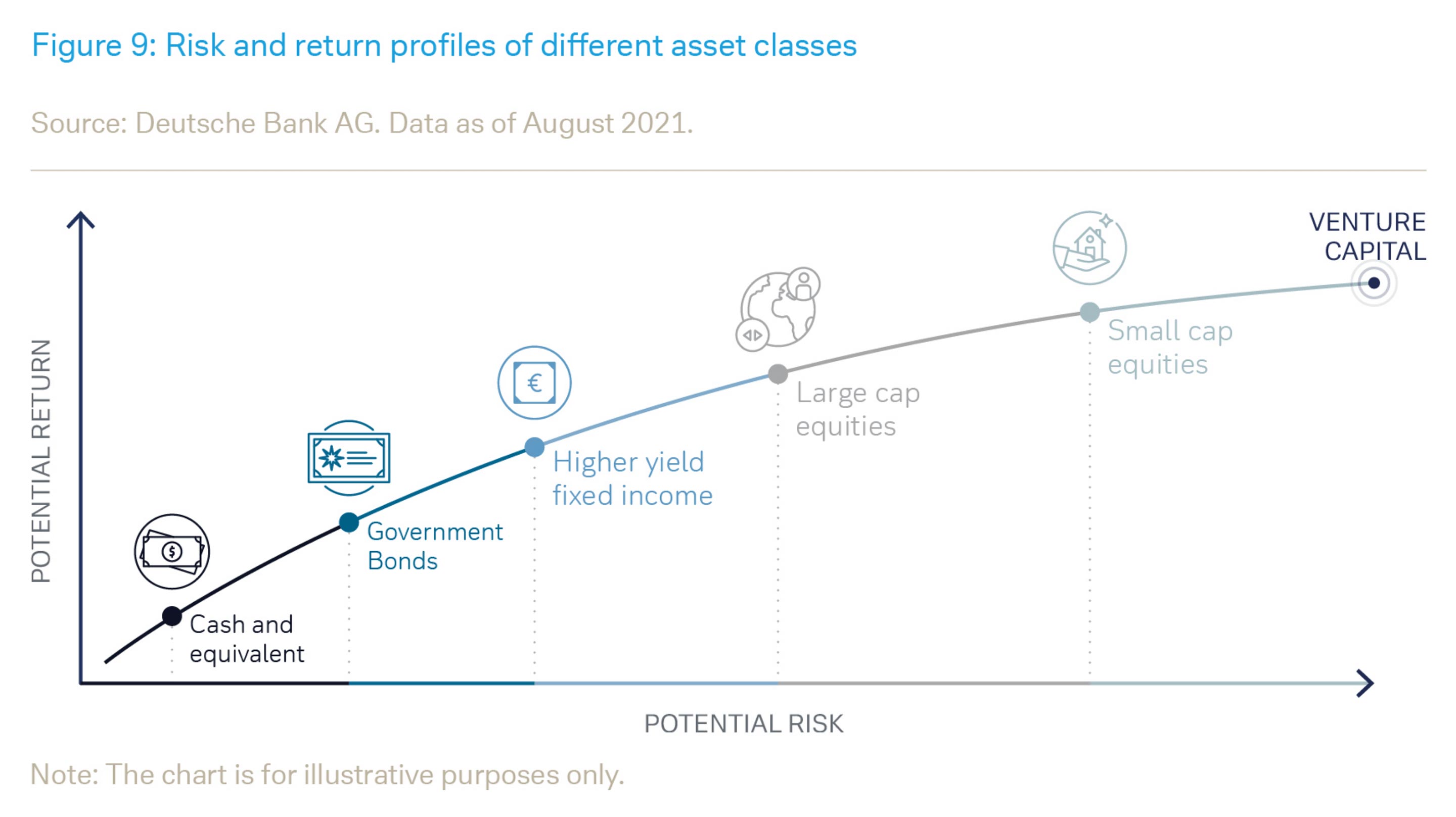

Investors may consider adding some Venture Capital exposure in accordance with their overall investment objectives and constraints to their investment portfolio. But it is important to be aware of the notably higher degree of risk which is associated with Venture Capital when compared to traditional asset classes. Figure 9 illustrates the risk/return profiles of Venture Capital and some major traditional asset classes.

We would like to outline two major risks in Venture Capital investing. First, this is a long-term commitment of Capital (typically locking up any investment for ~10 years).

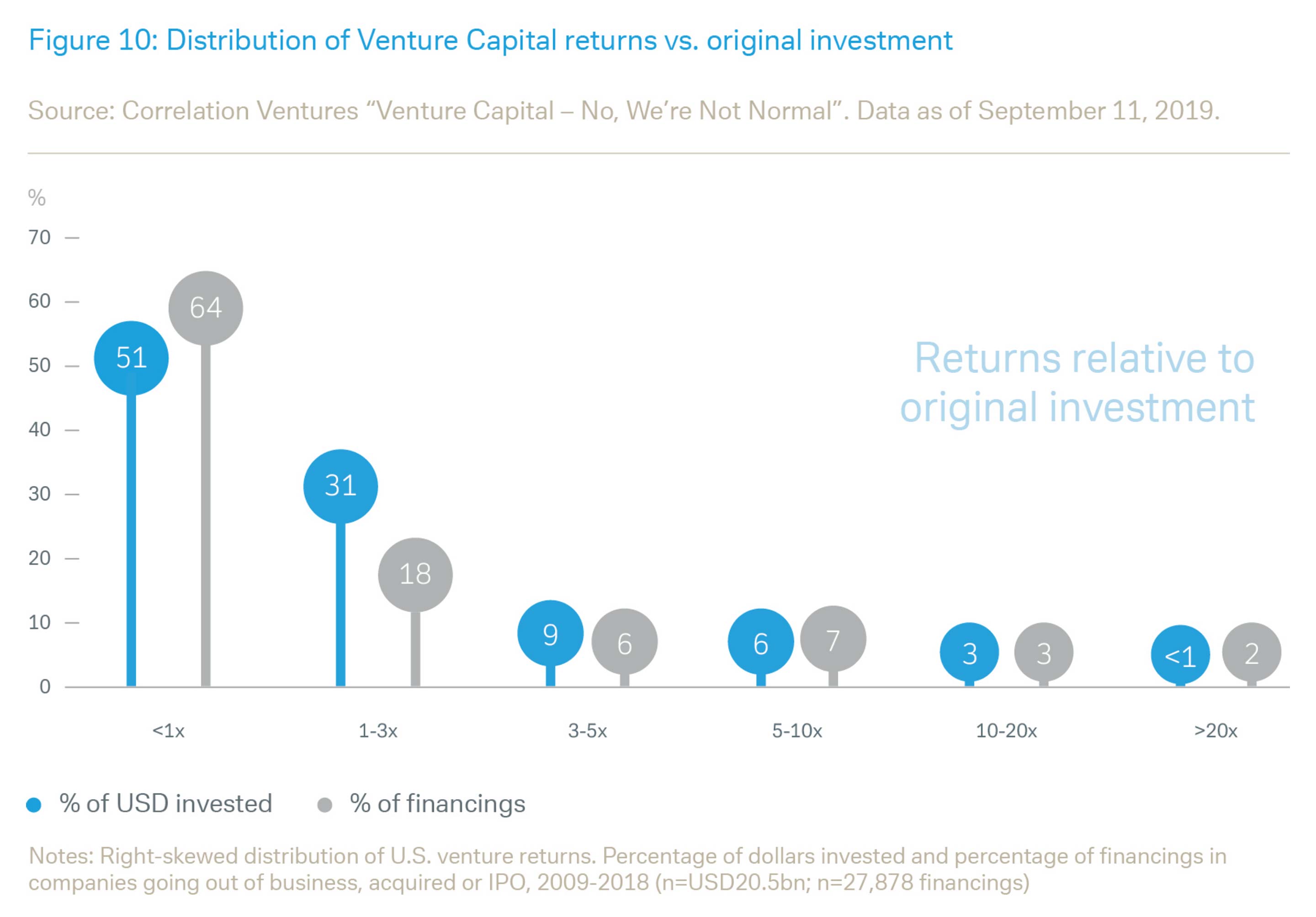

Second, there are substantial default or failure rates for early-stage companies. Over 10-year time horizon some portfolio companies may prosper, but the majority will not. A Correlation Ventures study which examined the outcome of over 27,000 investments (from 2009-2018) showed that 64% of Venture Capital deals did not even return the original principal (see Figure 10). As a rule thumb, Venture Capitalists tend to assume that two-thirds of the start-up universe will simply not return the initial investment or stagnate somewhere in the VC process, not being able to secure follow-up funding or to find an appropriate exit, respectively. Returns from Venture Capital investing will depend on the strong performance by the remaining third of companies that do well.

This implies that Venture Capital portfolios will need to include a wide range of investments. But it is not solely the number of eggs in the basket that is important. Diversification plays probably an even more crucial role in limiting the impact of investments that do not work, reducing overall volatility and risk, and improving the aggregate outcome. Investing into a broad range of industries across different stages (e.g., seed, early, expansion), regions and vintages can make an important contribution in this regard.

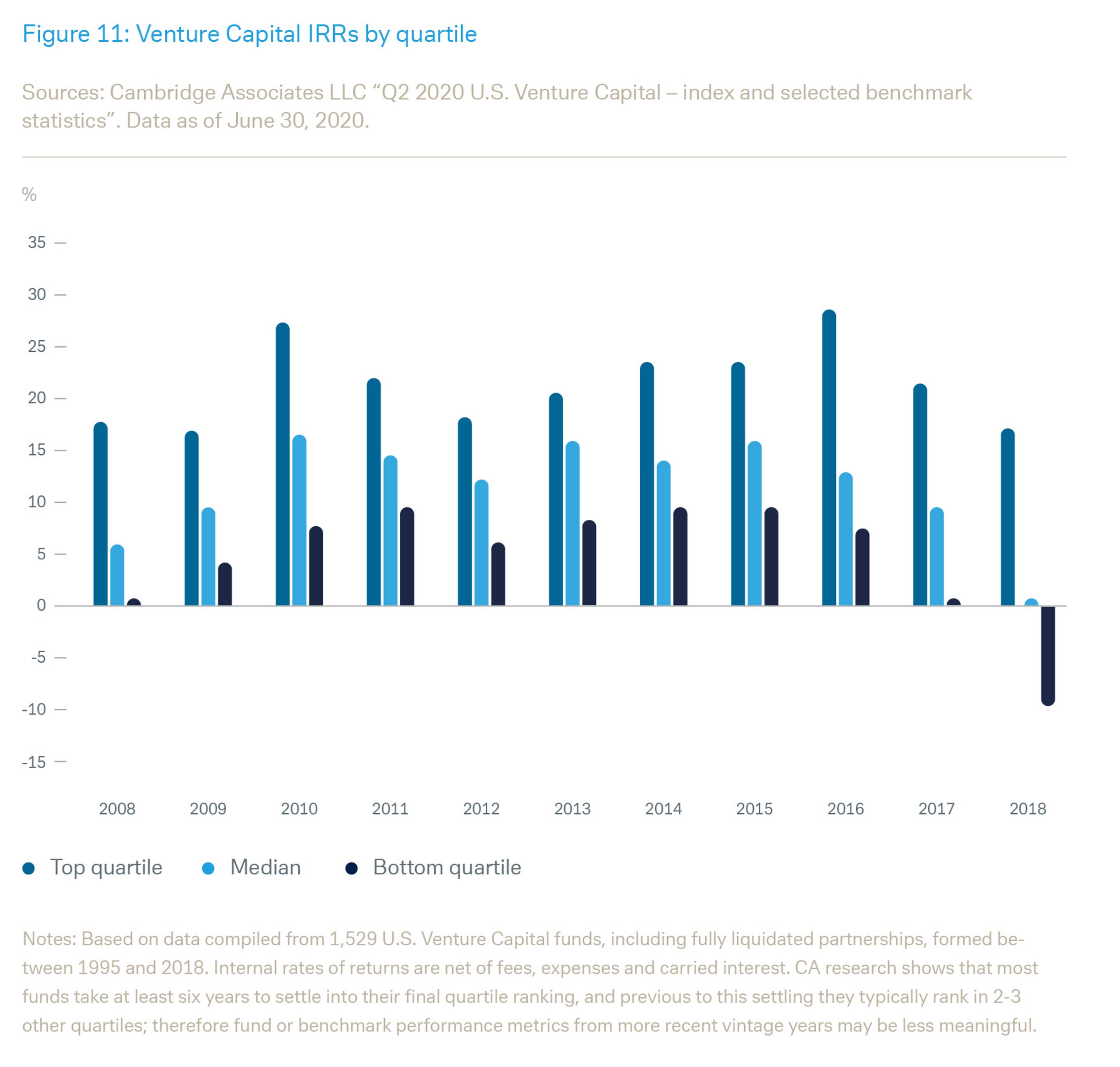

As well as this issue of diversification, it is worth returning to the point that top quartile funds consistently generate a disproportionate share of aggregate returns (see Figure 11). Unlike in most traditional (publicly-traded) asset classes, returns of VC investments tend to be very skewed. This makes it important to access the best-in-class VC investors.

For a brief summary of the report and to download the full PDF, please click here.

In Europe, Middle East and Africa as well as in Asia Pacific this material is considered marketing material, but this is not the case in the U.S. No assurance can be given that any forecast or target can be achieved. Forecasts are based on assumptions, estimates, opinions and hypothetical models which may prove to be incorrect. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. Investments come with risk. The value of an investment can fall as well as rise and you might not get back the amount originally invested at any point in time. Your capital may be at risk. This document was produced in August 2021. Readers should refer to disclosures and risk warnings at the end of this document. 050787 010722