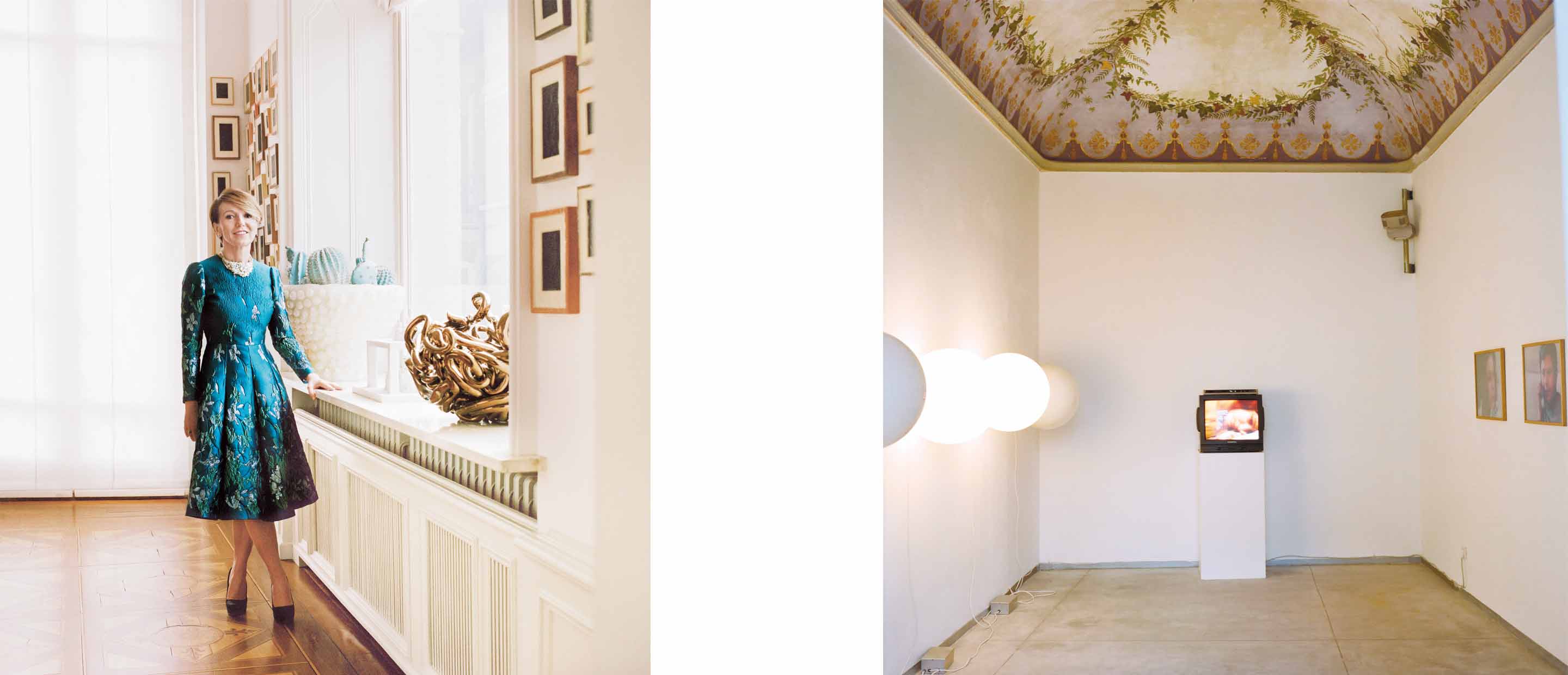

Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo is an art collector whose displays at her foundation and her home in Turin, Italy, combine visionary curation with a knack for discovering new talent. But her real focus is on education and introducing art to a wider audience, as we discovered during a visit to her creation in the Piedmontese capital.

I am standing in the entrance foyer of Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in a suburb of Turin, feeling a little disoriented. The trip to the foundation from the city center had been a journey from the sublime to the surreal, as the beautiful burnt-sienna tones of the Renaissance Savoy architecture morphed into a drive past an endless car factory, workers spilling out in their thousands, then a dystopian series of warehouses and basic housing, and, finally, a long, white contemporary building the length of a city block.

Inside, a curator had taken me on a tour of the current exhibits – my appointment was after closing time, so we had the place to ourselves. This included the astonishing but rather harrowing show, ‘Like a Moth to a Flame’, co-curated by Mark Rappolt, Editor-in-Chief of London’s ArtReview magazine; Tom Eccles, Executive Director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, New York; and the artist Liam Gillick. Including works by Maurizio Cattelan, Rachel Whiteread, Thomas Ruff, Damien Hirst and Carsten Holler, it was worthy of an art institution in any major metropolis, but also had shock value for its photography of mutilated war-victim corpses and its bomb-maimed female mannequins by Thomas Hirschhorn.

I am pondering all this while watching white foam ooze gently out of an installation in front of the reception desk, when a perfectly coiffed figure in a dark dress breezes up to me. “They have shown you around? Very good! What did you think?”

Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo quickly reveals herself to be a whirlwind, speaking crisp and virtually unaccented English at the speed of an Italian talking in their native tongue (she is also fluent in Spanish), exchanging ideas and suggestions at light speed. I quickly start to understand how this diminutive local woman – she was born into an aristocratic Piedmont family and married into another one – became a transformative philanthropic force in art in Italy (she has been described by Conde Nast’s W magazine as “Italy’s Peggy Guggenheim”).

The foundation is one pillar of Sandretto Re Rebaudengo’s activities; there is also a palazzo at Guarene d’Alba, southeast of Turin, which was the original home of the foundation until this new building was designed and constructed 16 years ago; and she has a rolling exhibition of emerging artists she is championing at her family home in central Turin, where she frequently hosts large dinners for the art and philanthropic communities. She is also opening a foundation in Madrid, which is to be designed by British architect David Adjaye and which will dwarf even her Turin building in size.

It is what Sandretto Re Rebaudengo does with all this that is interesting. More than just a philanthropist, she is an organizer and a central pillar of art education in Italy, of curatorial inspiration, and of support for young artists. She may look like a typical elegant, north Italian aristocrat, but she has a burning desire for the new – she collected works by the likes of Maurizio Cattelan and the Young British Artists in the early 1990s when they were fringe figures in a movement unknown to most of the world – and for changing the world for the better.

That is no empty overstatement. She personally organized and persuaded the Italian authorities into agreeing to allow her foundation to formally support the art education of children from across the country, and is planning the same for Spain. When I ask her if the next step will be Europe as a whole, her reply is quick-fire but careful, “Let’s just get Spain right first, and then let’s see!”

"You must give visitors the tools to approach, to understand and to interpret what they see"

Darius Sanai What were your original ideas and dreams about setting up the foundation?

Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo As a collector, I had the chance to meet artists and talk to them about their works. But this was the mid-1990s, a time when, unlike the rest of Europe, Italy still suffered from a distinct lack of institutions dedicated to contemporary art. I wanted to share this privilege I had with others as a way of giving back to society. I decided to become more active in the contemporary art world, by supporting the artists (both financially and by providing them with space in which to produce and show their work), as well as working to bring an ever-growing public closer to contemporary art. Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo was my way of doing that.

DS Do you consider yourself a philanthropist? What is important about philanthropy?

PSRR I created the foundation in 1995 for philanthropic reasons. As a non-profit institution our mission is to support artists and to raise their public profile, and to offer tools for understanding and programs for learning. The foundation is not here to house my collection, but to be a place for the arts, a laboratory for the production and understanding of new artistic practices.

DS What is the responsibility of an art collector?

PSRR Collectors play an extremely important role in the art system, primarily for the artists, because the support of a collector (especially in the early stages of an artist’s career) is essential to the production of their projects and to making their work visible. This is why I think it is necessary to be brave, to take risks and to seriously invest in the new. When you commission a new work, you don’t know what the outcome will be, but you trust the artist and take a bet on the future, which is the only way to really make a difference and be part of the artistic process.

In terms of offering a significant cultural experience to the public, I think that opening a space and making the collection visible is not enough. You must give visitors the tools to approach, to understand and to interpret what they see. Otherwise, the museum becomes just a showcase for the collection. This orientation towards education is important, and involves a lot of effort, research, experimentation and production of knowledge. I think that this is what a philanthropist should be dealing with.

DS You focus on understanding contemporary culture and observation. How do you do this?

PSRR I conceived the foundation as a kind of observatory from which to watch the artistic trends and cultural languages of our time, in the fields of art, music, dance, literature and design. Our priorities are the artists and our visitors. We choose to exhibit artists who, through their practices, are radically changing our vision of the world. The commissioning and production of new works is also very important to us.

DS The foundation has a strong educational element to its activities – why is this so important?

PSRR Education is a priority for me. Our educational work benefits children (from infants to teenagers), art academy and university students, teachers, people with special needs, families and adults. Furthermore, we believe that understanding the arts is a vital component of every person’s education and development. Contemporary art often uses unconventional methods, media and messages that push the boundaries of traditional art forms. We want to challenge people to discover how important it is to welcome these forms of thinking and creating in their lives, and let them provoke changes, reactions and reflections. Artworks and exhibitions, to me, are places for discussion and creation.

DS How do you create this space for discussion?

PSRR We have quite a radical way of interacting with our visitors, called art mediation. This has transformed the museum from a silent space where visitors have an individual experience to a place where points of view can be shared by establishing a dialogue on the major themes and issues of the world today.

Our ‘mediators’ are young professionals who have degrees in art or the history of art, and who receive ongoing training with us through a program of lectures, workshops and meetings. Art mediators are provided by the foundation as a free service, in order to facilitate the relationship between visitors and the artworks. They provide information about the exhibitions, helping to create a dialogue about the works and allowing visitors to foster their own personal reflections.

DS Accessibility seems to be important to what you do at the foundation.

PSRR Yes, accessibility is key for us. It goes beyond the architectural structure of a museum and represents the right for everybody to have access to culture. This is why social media is extremely important to us, as it enables us to create interesting short circuits with a great communicative impact. We try to stay tuned in to what’s happening in both the real world and the virtual social media world because, to communicate contemporary art effectively, it is necessary to speak the language of contemporaneity.

DS What are the challenges, then, of reaching a generation brought up on electronics and social media?

PSRR We believe that what art can bring to the way young people live their lives can provide them with a more critical approach to the world around them and teach them to question what they hear and see. I believe art can help them understand how such things as smartphones or social media can be used in a more aware and conscious way. For example, work with 16-year-olds on Thomas Hirschhorn’s piece 'Ingrowth' led to a beautiful and profound conversation about how images are used in the media nowadays, about who decides what we need or don’t need to see, and what the connections are between art and economics, violence and information. Such reflections among teenagers are priceless, and contemporary art gives them a space for confrontation and personal growth.

"Artworks and exhibitions, to me, are places for discussion and creation"

DS The foundation is also committed to supporting people with special needs. How?

PSRR Museums have a social responsibility. I like the idea of my museum – of the foundation – as a place where everyone can share a point of view, however ‘special’ the condition he or she lives with. Contemporary art talks about – and to – our whole society, and can be an instrument for understanding people better. A museum should be a place where being different is valuable. So we create situations in which people with very specific needs can feel comfortable. But we also work a lot to champion social inclusion. We do this by organizing activities at which people with (or without) disabilities can meet and work together.

DS What kind of program does this include?

PSRR The visually impaired, for example, have specific tours where they can touch some of the works. Where that is not possible, we use reproductions. We are also working on a very experimental path, organizing meetings with blind and deaf people, trying to communicate art beyond disability, considering mainly what they have in common. Individuals with intellectual or cognitive disabilities can also find in our museum a welcoming and familiar space, where they are able to express themselves according to their individual abilities and needs.

DS The foundation has supported the production of ambitious exhibitions, such as Doug Aitken’s 2002 solo show New Ocean. As a privately run non-profit institution, how do you raise the funds for projects such as these?

PSRR The foundation is mainly funded by my family’s donations. We receive additional support from the Regione Piemonte on specific projects, as well as from the two charitable institutions of banking origin in the region, Compagnia di San Paolo and Fondazione CRT, mainly for our educational activities. In addition to that, we seek partnerships with institutions for specific projects.

DS The foundation supports all kinds of art, including producing the 2006 film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait. Is there a medium you prefer?

PSRR I have always been very interested in video art, first as a private collector and then with the foundation. It began in 1999, with the production of Electric Earth by Doug Aitken, a multi-channel video installation the artist presented at the Venice Biennale and which won him the Biennale’s International Prize. Incidentally, two years later we also produced Aitken’s New Ocean, which was commissioned by the Serpentine Gallery in London.

In 2007, we presented Stop & Go, a group exhibition entirely devoted to the medium, which involved the commissioning and production of several pieces. We have supported numerous similar projects over the years, either as producers or co-producers.

DS You also launched the Young Curators Residency Programme in 2007, and Campo, an independent course for Italian curators in 2012 – it seems you place as equal weight on supporting curators as you do on the artists. Why?

PSRR The Young Curators Residency Programme is one of the ways in which the foundation seeks to support Italian artists. Every year, three young curators, selected from major art schools from around the world, are chosen for a four-month residency. They travel to Italy, meet artists, curators and museum directors, and visit artists’ studios and galleries. The group curates a final exhibition, featuring the work of the artists they met during their trip. The residency has the dual objective of developing the professional and intellectual skills of young curators in the early stages of their careers, and of taking Italian contemporary art into a more international context. We also hosted an international symposium on curatorial practices in 2016 to celebrate this program’s success.

DS As governments become poorer, does philanthropy become more important? Is it working well in general?

PSRR In Italy, over the past 20 years, private museums and institutions have played an integral role when it comes to art, as they step in to compensate for a decrease in public funding in the support and promotion of young artists. We should not forget, in fact, that the first national museum for contemporary art, MAXXI in Rome, opened only in 2009, so Italian private institutions have played an important role in supporting the artists and bringing contemporary art closer to a wider public for a long time.

"A museum should be a place where being different is valuable"

DS The foundation is opening in Madrid. Why there and why now?

PSRR I wanted to broaden the scope of the institution I founded in 1995, and place it in the context of a major European capital. I chose Madrid because I consider Spain to be my second home, and because Spanish is a language I know well. Madrid is a big, global capital and a bridge to Latin-American culture, a growing scene that I have been watching closely for a long time.

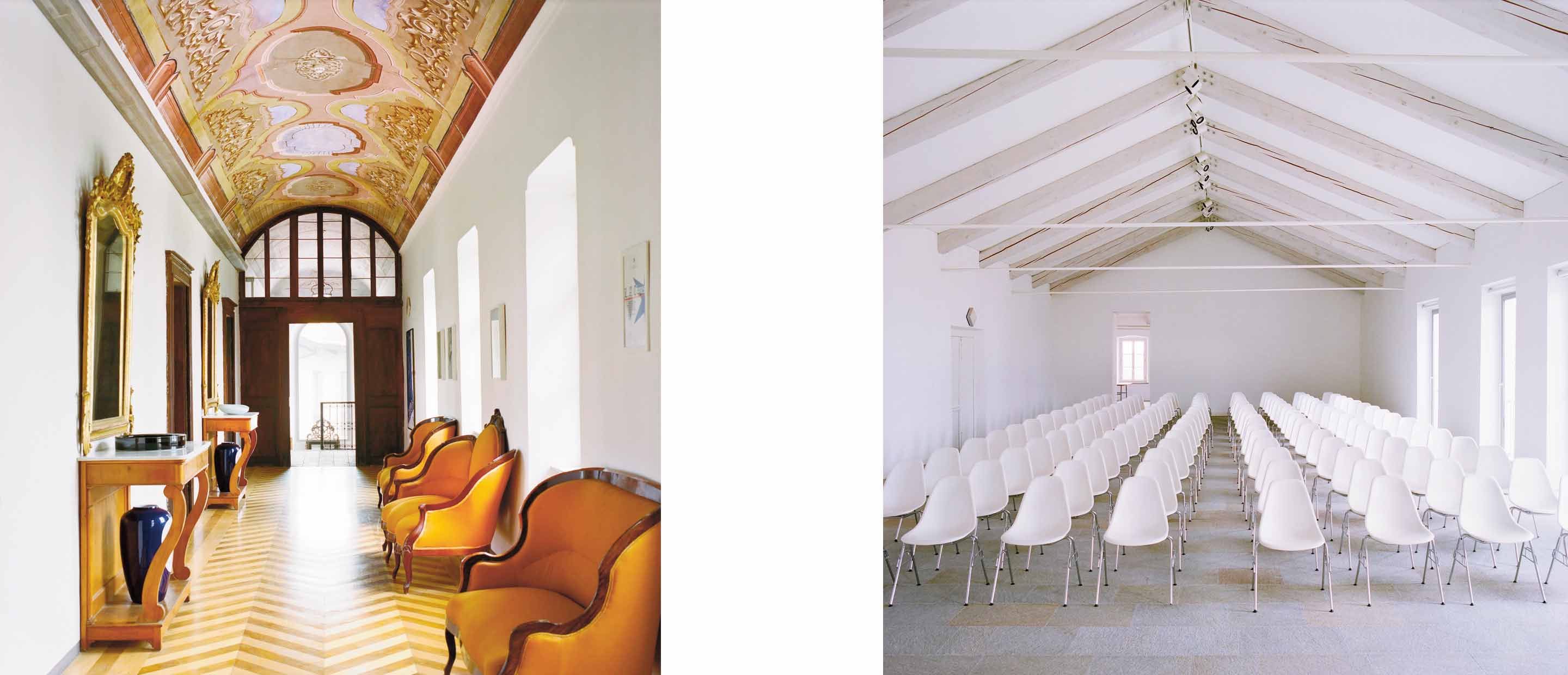

I like to think that the institution that bears my name, and that of my family, now has three homes connected by a clear, coherent philosophy, yet with defining features of their own: Palazzo Re Rebaudengo in Guarene d’Alba, which opened in 1997 in an 18th-century palazzo; the Fondazione here in Turin, which was designed by the London-based Italian architect Claudio Silvestrin and which opened in 2002 in a district that has spearheaded the dynamic transformation under way in my city; and now Madrid, where the Fundacion will be located at the heart of the Centre for Contemporary Creation, a true laboratory for multidisciplinary work. These three sites are all attuned to the spirit of contemporary art and its ability to move between the local and global, and the natural and urban landscape.

The Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Collection will play a major role in the new Fundacion. My collection has always been open and vital; it forms the basis for the foundation itself and, in its 26 years of existence, it has traveled all over the world. In Madrid, the collection will be divided thematically to showcase works of internationally acknowledged artists created between 1990 and today, with a focus on artists who have not been shown so much in Spain to date. It will also feature spaces for an educational department, for cultural mediation, specialized training, and artist and curator residencies.

DS Can your philosophy be expanded worldwide?

PSRR Definitely, yes; never say never.

Darius Sanai is an Editor-in-Chief at Conde Nast and Editor-in-Chief and Publisher of LUX magazine. This article originally appeared in the May 2018 International edition of Werte, the client magazine of Deutsche Bank Wealth Management.