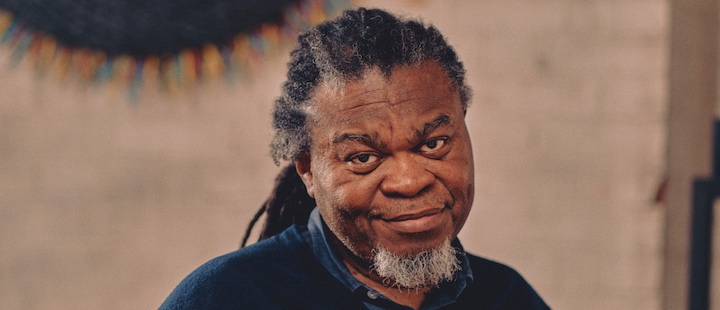

The work of South African photo and video artist Mikhael Subotzky, born in 1981, is about artistically processing the history of colonialism and apartheid, experiences of masculinity and patriarchy. To do this, he goes into prisons or deconstructs the stories of colonial commanders and museum guides.

Subotzky became internationally known in the mid-2000s for his large-format colour photographs and monographs dealing with issues of imprisonment and punishment in post-apartheid South Africa. Subotzky portrayed inmates, such as those in Cape Town's maximum-security prisons, but also captured the architecture, which itself reflects the legacy of structural violence. For example, he photographed the infamous Ponte Tower in the city center of Johannesburg, built in 1975 as a luxury apartment complex and then taken over by gangs who made it the most dangerous place in the city and a symbol of violence, prostitution, and segregation.

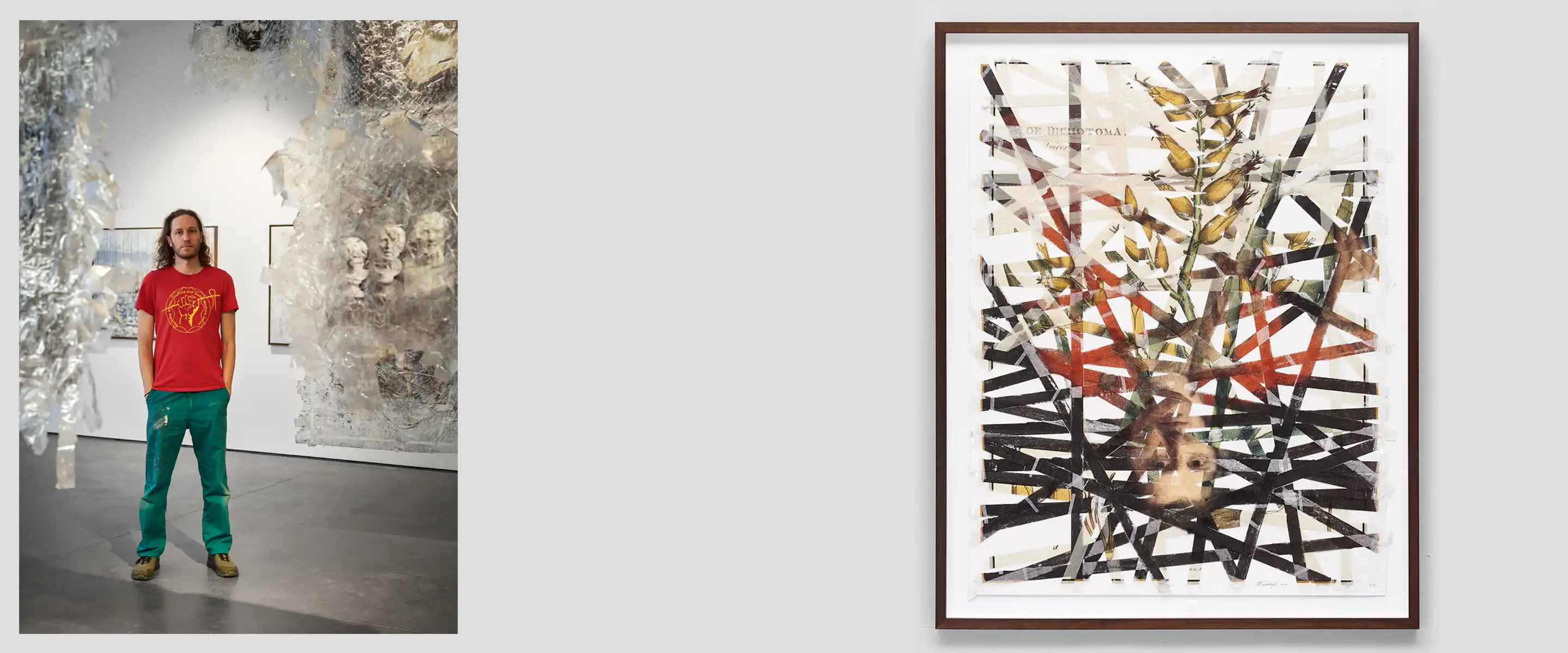

Subotzky’s shift in format: from photo to film and collage

As he turned to filmmaking in 2012, Subotzky's practice became freer, formally and poetically exploring the power of vision, images, memory and the contradiction between collective and subjective experience. For his ongoing series of so-called “Sticky-tape Transfers”, he manipulates his photographs with tape and glue, literally shattering and deconstructing the typical window-like surface of his photographs. This is the case with "Sticky-tape Transfer 13, Quiver Tree / Robert Jacob Gordon" (2014), a work from the Deutsche Bank Collection that deconstructs and kaleidoscopically intertwines two images cut into strips: a portrait of the Dutch explorer, officer, artist and scientist Robert Jacob Gordon (1743-1795) and one of his botanical drawings of a quiver tree. Gordon, the colonial master, is a complex figure. He undertook more expeditions than any other explorer of southern Africa in the 18th century. As well as French, Dutch and English, he spoke the indigenous languages Khoekhoe and Xhosa. Between 1780 and 1795 he commanded the garrison of the Cape Colony. Because of a political intrigue in which he made the mistake of allowing a British fleet to occupy the Cape, he was accused of treason by his own soldiers. Exiled and threatened with violence, he took his own life in 1795, a victim of the system he had faithfully served.

Exploring the space where institutional and personal memory collide

Experiences of masculinity and patriarchy are central to Subotzky's work. This is also the case in his four-channel video installation “Moses and Griffiths” (2012), just shown in the exhibition “The Struggle of Memory”, which deals with colonial history, the gap between official and personal memory and the possibility of other narratives. "Moses and Griffiths" is a cinematic portrait of two buildings and two men in Grahamstown, a small South African town with a strong English colonial heritage. Both men have worked for many years as tour guides in historic buildings. Moses Lamani guides through the nineteenth-century camera obscura at the Observatory Museum. Griffiths Sokuyeka does the same at the 1820 Settlers' Monument, a modernist structure built in the 1970s to “protect” the English language and culture in South Africa. Subotzky first had the men give their standard tours, telling institutional histories. He then asked them to tell the story from their personal perspective, deconstructing both versions into a cinematic narrative whose structure is reminiscent of his "Sticky-tape Transfers". The result is a meditation on the relationship between institutional and personal memory – and the dichotomy created when they collide.

About this article series

This article forms part of a special series celebrating Deutsche Bank’s 20 years as Global Lead Partner of Frieze art fairs, taking a closer look at one of 20 artists we have collaborated with and whose work features in the Deutsche Bank Collection.

Deutsche Bank's commitment to art and culture

Deutsche Bank is the Global Lead Partner for Frieze art fairs, with 2023 marking the 20th year of the partnership. As part of its Art & Culture commitment, Deutsche Bank has supported and collected the work of cutting-edge, international artists for more than 40 years. A global leader in corporate art programs, the bank also runs an Artist of the Year programme, as well as its own cultural centre in Berlin, the PalaisPopulaire. All initiatives are based on the strong belief that engagement with art has a positive impact, not only on clients and staff but also on the communities in which the bank operates. Thus further collaborations such as the Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award in the United States, The Art of Conversation in Italy, the Frieze x Deutsche Bank Emerging Curators Fellowship in the United Kingdom, and the digital platform Art:LIVE, create access to contemporary art for people all around the world. Discover more here.

Please find more information on Deutsche Bank’s art programme at db.com/art and follow us on Instagram @deutschebankart

Main image: Mikhael Subotzky, photo by Alexander James Edwards (detail).

Developed by

Deutsche Bank Art & Culture