José María Figueres has pioneered the integration of sustainability, technology, and the public and private sectors in the service of the environment. The former president of Costa Rica and businessman speaks to LUX magazine about the future of the oceans in the shadow of the pandemic.

LUX: How will the pandemic affect environmental and sustainable policies?

José María Figueres: This crisis has clearly made the link between our health and the health of the environment. More and more people are convinced that in our treatment of the environment, in our slash-and-burn approach to so many habitats and so many species, we have brought down the natural barriers that protect humanity from the many viruses and other illnesses that are out there in other animals. So, I would hope that means that the environment will be more on the front line of our thinking coming out of this crisis, and for the better, too, not just for keeping the status quo.

Climate change and the ocean are two sides of the same coin. You really cannot fix one without tackling the other. On one side, the ocean is the most impressive vacuum cleaner in terms of sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and giving us back oxygen, every second breath in your life and mine. On the other, if we don’t reverse climate change, we are going to be adversely affecting the ocean and its capacities because of the increased absorption of carbon and the consequent acidification.

I think that the overriding objective here is to ensure that everything we do is driving towards net zero. This means the way we live, the way we organise, the way we work, the way we transport, everything. How do we go towards net zero? That is where the most important business opportunities are going to be in terms of a sustainable blue economy. And when we speak about innovation in this realm of possibilities, I think that there are two areas in particular where you can see it taking place.

One is the world of finances, where we are seeing a lot of new ideas and private financing coming in. This can be seen in the way that funds around the world are looking much more closely at the carbon footprint of their investments, and blended financing tools that are coming up, even in the world of insurance companies. So, they stand to lose or gain a lot, depending on how climate change goes and its effects on the ocean and rising sea levels. One of the positive experiences at [the ocean advocacy group] Ocean Unite has been working with AXA, the insurance and reinsurance company. From our first meeting in Bermuda three or four years ago, that work has grown into the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance, a global partnership with support from the Canadian government and many other finance and insurance companies, countries and non-profits. We came to this from an environmental perspective at Ocean Unite and from a financial one at AXA, and together we examine how the world of finance and insurance can play a positive role in sending markets the correct signals to reduce ocean risk and invest in nature to grow resilience to change.

The other area where we can see a lot of technological evolution is in advancements in technology itself. Global Fishing Watch, to mention just one group, is now using advanced AI, algorithms and satellite imagery to control illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, which is devastating fish stocks around the world. With such technology, along with the Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA) signed up to by almost 70 countries, we can now begin to have more tools to control IUU fishing.

LUX: Will consumers pressure companies to show their sustainability credentials?

JMF: I would hope that coming out of this crisis, in spite of the pressures on the finances of so many families and a hard-hit world economy, we would begin to recognise the importance to our lives of favouring products that are made with environmental considerations by companies who are upholding these standards and moving towards net zero in countries that have regulatory frameworks. But this shift towards net-zero carbon is not something that can be the responsibility of just governments or the private sector. We all have to be in this together. At Ocean Unite, we like to say the ocean is everybody’s business. Whether you live next to the ocean, or far from it, or even if you’ve never even seen it, it’s your business, because it’s the most important ecosystem in our lives. With no ocean, there is no life on the planet – the planet will go on, but not with us.

LUX: In terms of the blue economy and innovation, what interests you especially?

JMF: Tourism is a particular word associated with the ocean, whether it’s because we’re sailing, or on cruise liners, or just taking a normal vacation by the sea. There are many ways in which the tourism industry is now beginning to change, having been so hard hit in this pandemic, to come back much better than before, with a lower carbon footprint, increased respect for environmental considerations that goes through their infrastructure to the way they are purchasing their food and processing it.

Another area is shipping. There are 55,000 or 60,000 ships out there that are holding the world’s cargo. Their aggregate carbon emissions is the equivalent of an economy somewhere between the size of Japan and Germany. Now, those ships need to go into dry dock every five years, and if you take advantage of that moment you can deploy a suite of between four and eight technologies on them. Depending on the ship, that’s an investment of between two and four million dollars. You can put new paints on the hulls to reduce friction in the water, saving them fuel; you can install new software that helps the ships navigate a precise course without two or three degree deviations. And you can put other, more complex technologies on board that are going to save you, depending on the ship, between 10 and 15 per cent of their fuel, which means 10 to 15 per cent less in the way of carbon emissions.

The paybacks on those investments could be anywhere between nine months and three years. That type of a return on investment is fantastic in any economy and much more so in this one. So, I think it’s a combination of, on the one hand, governments understanding what the best regulatory frameworks are, and on the other markets to invest in this direction. And from the private sector, taking advantage of those opportunities to come in with what the business world has, such as access to capital, creativity, innovation and new business models, including how to move to zero-emission shipping.

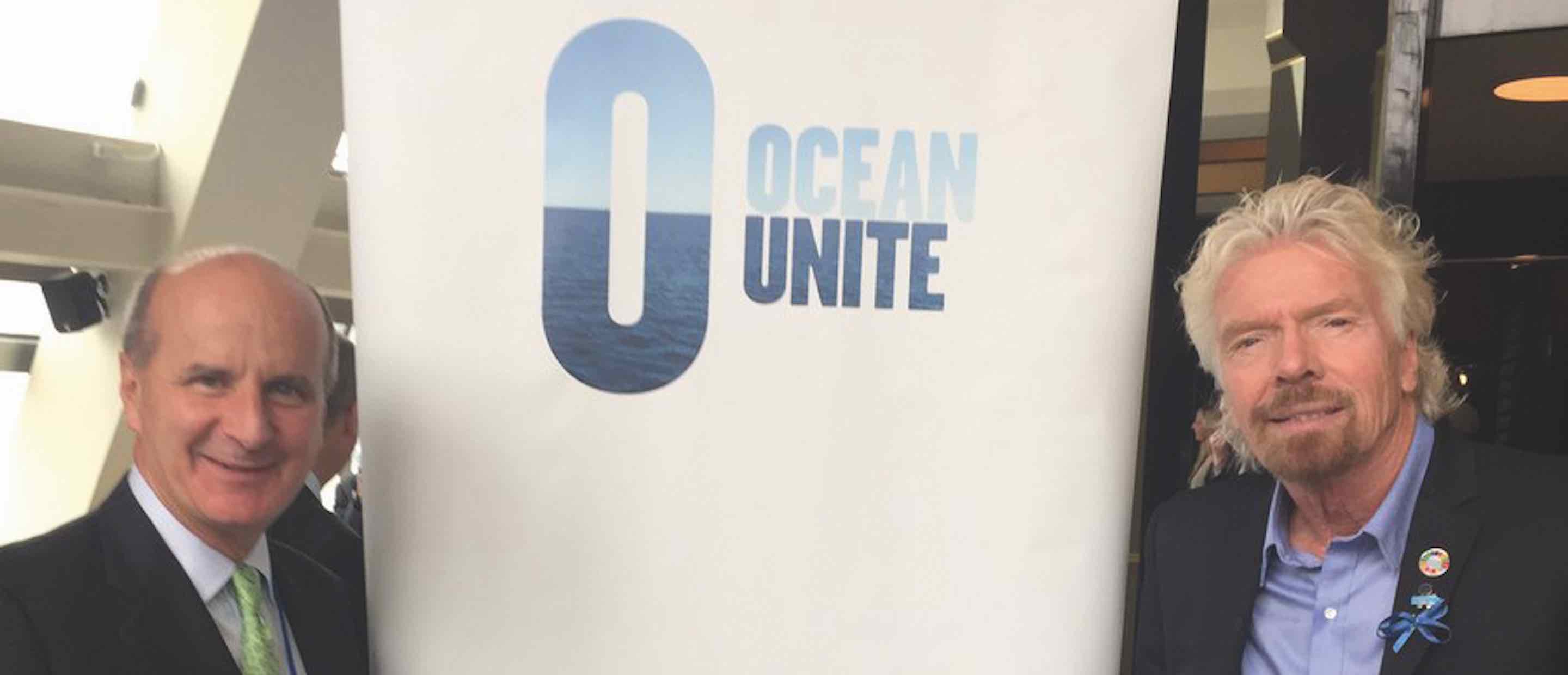

There are some fantastic CEOs out there who have been showing movement in this direction for some time now and who continue to do so. Richard Branson, in my world, has been an inspiration because of his preoccupation with the ocean and climate change and what he personally has meant in terms of leadership and help. After the two devastating hurricanes that came through in a matter of weeks in the Caribbean, he has almost single-handedly pulled together the Caribbean Climate Smart Accelerator to rebuild the region in a climate-smart fashion so that it’ll no longer succumb to the storms caused by climate change.

I was on a panel just two days ago with Marc Benioff at a World Economic Forum (WEF) meeting. Marc is the founder and CEO of Salesforce, a company that you’d think has nothing to do with the oceans. And yet he has become such a passionate advocate for them. He is all about his company and inspiring others to go to net zero, and he’s very concerned with creating greater awareness of the importance of reaching 30 per cent protection of the oceans by the year 2030 (which sits at the core of Ocean Unite’s mission), meaning establishing marine protected areas, which is what the scientists tell us we need to do if we want to restore the ocean’s health. He’s also a strong advocate of the WEF’s support of the Trillion Tree initiative because so far, in spite of all of our technology, we haven’t been able to beat nature when it comes to developing an efficient, low-cost way of taking carbon out of the atmosphere and turning it into something useful.

LUX: How does the world bring China on board? And do you see that happening?

JMF: If you look at what has been happening in recent years, one has to admire what China has done in terms of renewable energies. Using economies of scale, it has brought the cost of wind turbines and solar panels down by more than 80 per cent in the past decade. It has also recently agreed to carbon neutrality by 2060. But you have to consider China in relation to the ocean. China is a big consumer of ocean products, and is one of the few nations to have a fishing fleet on the high seas. So, the COP15 celebration at the UN Biodiversity Conference was due to take place in China in autumn 2020. It was supposed to bring the world together to agree on a global deal for nature for the next ten years, including adopting the 30 per cent protection target on land and at sea. But it has been rescheduled to later in 2021. China could take advantage of being the host to lead by example and pick things that are crystal clear in terms of the benefits that they can bring but at a relatively low cost to humanity.

For example, Antarctica. Most of the biodiversity there is found in the incredibly rich waters that surround the continent. Nothing lives inland because of the climate, but more than 9,000 species call those waters their habitat. Life begins there with the micro plankton and continues up the food chain that is taken by currents to the oceans around the world, becoming the food for 40 to 50 per cent of the total ocean biodiversity. The same currents help stabilise of our climate system.

For several years, countries have been discussing protecting three very large marine protected areas around Antarctica – the east Antarctica MPA, supported by France and the EU, Norway and Uruguay; the Weddell Sea protected area supported by Germany and the EU, Norway and Uruguay; and the Antarctic Peninsula supported by Chile and Argentina. Together they would comprise almost four million square kilometres, which, if they were supported by all the countries that are part of the international treaty that regulates this area, would become the single most important act of ocean protection in history. Only two countries stand in the way of a consensus decision. China is one and it could take a leading role in this year, which is the biodiversity year, to start moving in the direction of saving our biodiversity.

My take on the blue economy is that from the basis of the normal economy, if I may call it that, we started talking about the green economy incorporating the environment. And now we’re talking about the blue economy, which incorporates it all. So to me, whether you are linked to the ocean or not, you are part of the blue economy. If you can lower your carbon footprint, you are having a positive impact on the ocean and that makes you part of the blue economy. We now understand the links between economics, health, environment and ocean, and we see more clearly how they come together. We can consider ourselves all part of the blue economy.

LUX: You chair Ocean Unite. What are its plans over the next five years?

JMF: Our mission statement is ‘30 by 30’ – we want to see at least 30 per cent of the ocean under protection by 2030. It’s clearly stated in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG14) that we were supposed to have conserved 10 per cent of the ocean by area by 2020. We’re going to miss that, understandably, but now we have to climb up exponentially and reach 30 per cent in the next decade. At Ocean Unite we’re also working together with the Oceano Azul Foundation and other organisations to build a movement called RISE UP – a Blue Call to Action that everyone in the ocean community can adhere to. More than 450 organisations have already signed up to this incredible network. We also look forward to continuing our work with AXA on ocean risk. And lastly, we are a founding member of Antarctica 2020, a group of global citizens who understand Antarctica’s role in the health of the ocean and who are fully committed to seeing marine protected areas in the sea around the continent, including those three proposed marine protected areas I mentioned earlier. Those three cover just one per cent of the ocean’s surface, which is huge, but also small in context. My dream is to see all the ocean around Antarctica converted into a marine protected area in the next few years, so no fishing and no mineral exploration.

LUX: My daughter wants to ask you what her generation can do to help the future of ocean conservation.

JMF: I think you first need to start thinking about adding in a colour – blue – to include the ocean. And you can play an important role in several ways. Firstly, there is a need for a greater understanding of the role of the ocean in our daily life. Secondly, we all, wherever we live, have a role in restoring the health of the ocean because one of the worst effects on it is climate change. Our lifestyle produces increasingly more carbon that is then absorbed by the ocean, warming it up and increasing its acidification, which is killing coral reefs, half of which have died in the past 50 years. During the pandemic we have seen nature return so fast during the economic slowdown. We have to get back to normal in a way that allows nature to exercise these healing powers further by producing less carbon. So, save energy, use public transport, choose less carbon-intensive diets, and use your voice. The ocean is rising and so we must get politicians and businesses to support biodiversity and carbon neutral action – and quickly. There really are many things that can be done to help the ocean and we all have a part to play.

oceanunite.org

This article first appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of LUX Magazine. This issue features in the third in a series of Deutsche Bank Wealth Management/LUX supplements about our ocean and its importance to both the environmental and economic wellbeing of the planet.